In February of 2018 I was hosted at a guest house located at the entrance of the city of Alaverdi. When I got there, it was already getting dark, I stood for a moment in front of river Debed, which seemed like a huge, blue dragon, that was running madly towards the depths of the city. The city, though, was not in my sight from where I was standing, it was hiding behind the mountains, and only the huge chimney of the copper smelting factory was visible. Though I was rather far from that immense pipe, I was feeling myself inside a smokey bag. The smoke was everywhere, it seemed to me that it was the owner of the city, the people, of everything. With those impressions of darkness I came back to Yerevan. The decision of returning back to Alaverdi lasted so long, that the copper smelting factory closed down in October of 2018. It was hard to imagine the city without smoke…

“Many leave the city. What will they do if they stay in these ruins?”

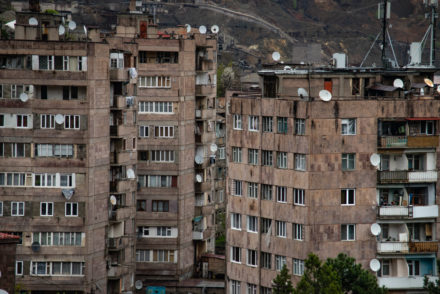

The city and factory buildings are left without care.

“It’s because of the factory, maybe, the people here have many illnesses, bone pain. They go to examine their health and discover they have cancer, for example the husband of my neighbour.”

In the area of the copper smelting factory there appear many puddles containing different metals after the rain. They witness that the factory has an impact on the environment with dangerous materials.

The buildings of Alaverdi built in Soviet times

Details in the city and the factory.

In February of 2019 I return to Alaverdi. The first place I go is the station of the ropeway in the neighborhood օf Sarahart. The view from there… The crooked, worn out roads messed with empty, uncolored buildings is like a labyrinth with no exit… I don’t know, maybe the day was gray, or the city was in its depressive waiting, and the factory was like a rusty mass in its heart.

And a traditional scenario… Someone appears, who wonders who you are, what you are doing in the city, why you take pictures. And just one question is enough for him to tell the whole story of the city. “During Soviet times, Alaverdi residents had status, the factory was for the city, and the city for the factory. Now they broke the back of the city, 600 people remained without jobs, that is very serious for a city this small. The workers have blocked the roads for several times for the factory to open again. Do you understand? People have loans, someone has repaired his house with a loan, the other has played a wedding, the third has had a surgery. Don’t they have cancer in Yerevan? Yes, smoke is not good, they must supply the factory with filters, but who thinks about people? What about now? There is no smoke, but also no people to breathe clean air.”

“Grandpa, don’t you remember anything good from the factory?”, “No, it’s just the smoke, that I remember.”

The former metallurgist grandchild asks his converter grandfather.

The sitting room of a house in Alaverdi.

“They thought of us neither when closing down the factory, nor now.”

A city view from the neighbourhood Banavan.

Working environments.

“Tourists like you come, take pictures.”

The station of the ropeway of the neighbourhood Sarahart. Mostly tourists visit this sight.

Factory details. They look worn out and old.

I have wandered in Alaverdi for several days, have got acquainted with people, got lost in the yards, sat and silently followed the flowing life. It’s not that the city is empty, and everyone has migrated. Alaverdi locals love their land, water, air. They love, but also neglect their poverty, shabbiness. They don’t know in what language to say I won’t buy bread with clean air, won’t buy medicine, won’t pay out my loans. Not that everyone agreed with the smoke either. They were choking even at home, but they lived silently, because the smoke was stable. People would go to work in the morning, they knew where, and for how many hours, what they needed to do. If they didn’t have a worker at the factory, they had a neighbour, who worked at the factory and would buy bread from them at the end of the day. The woman of the bread booth answered my question of how is the business – ah, dear, they buy less bread now, Alaverdi has become a sad, worn out and hungry place.

P.S.

They ask to an Alaverdtsi where will we go when you get your salary? He answers, we will go by, just go by.

“People have no money for bread.”

The cafe Drakht (Heaven) is located in front of the factory. It works in summer months, and was more active, when the factory was working.

The factory of Alaverdi provided some stability to the residents, but many of them have serious health problems now.

“The revolution has not entered Alaverdi.”

The road connecting to the factory at the end of the day.

Views from the copper smelting factory and the city.

“The ropeway got destroyed, no one cared.”

The ropeway of Alaverdi does not operate since 2014, the wagons are hanging in the air until now, which is very dangerous during the winds, but the municipality doesn’t have money to renovate it. The ropeway connected the neighbourhoods of the city to one another. Now people use the city transport instead, which is an extra expense for them.

“This photo story was funded through a Department of State Public Affairs Section grant, and the opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed herein are those of the Author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of State.“