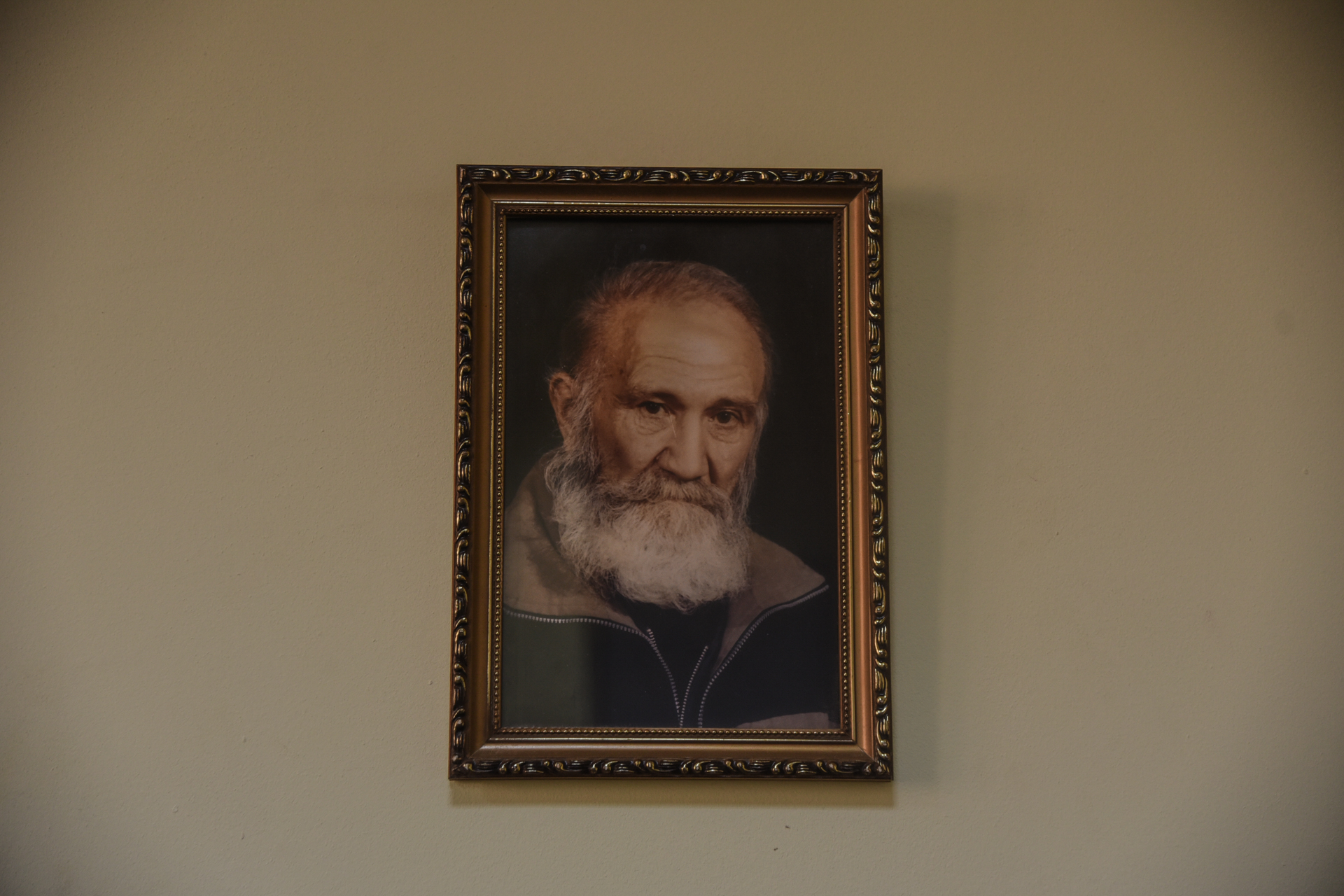

Who was Udi? The Robin Hood of our time, who loved Yesenin, listened to Beethoven, and dreamed of a “golden city” where honest people with high morals would live. The best years of Udi’s life were spent behind locked doors, which were opened only in his old age. One of the most famous thieves in the world of crime lived the last 13 years of his life in the nursing home in Nork, receiving a monthly pension of 13 000 dram (about USD$26).

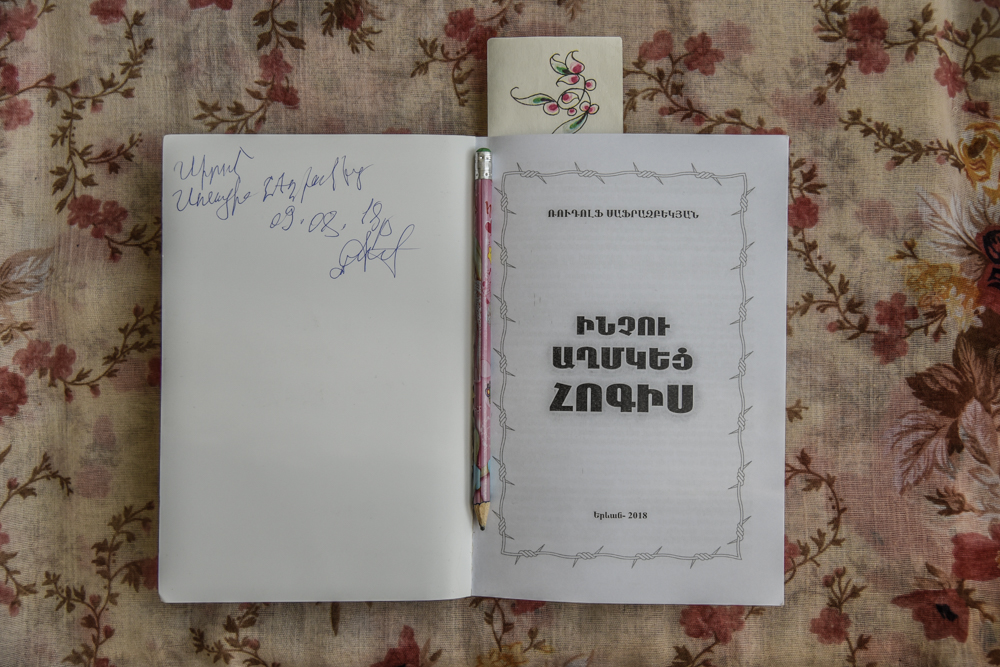

The first thing that attracted me to Udi was numbers: 15 convictions, 45 years’ imprisonment, and all that during 80 years of his life. I became acquainted with Udi — Rudolph Safrazbekyan — at his book launch. Why My Soul Cried Out is his second autobiography,(editor Ruzan Minasyan) a record of his time in prison. I was affected by the contrast between those numbers and what I was seeing, especially when I met small-framed Udi, sitting on an oversized armchair, puffing and panting heavily and talking in intervals.

Some time later, I went to visit Udi at the nursing home in Nork. His health had deteriorated; he was constantly repeating, my lungs have dried out, but shortly after, he became livelier, we began to talk, to laugh. “I like myself a lot. He who doesn’t love himself doesn’t love people,” he says and continues: “I’ve lived rightly and have not regretted anything.” I’m a little surprised by such a confession. “There is only love. Respect is a contrived word; it was invented so it can fill that empty space where love should’ve been.” He takes a break and shortly after adds, shoot whatever you want. Udi replies to my questions succinctly; he says, read my book and you’ll find out. And so we agree: I promise to come next time having read his book.

“To Sona with love from the author. August 9, 2018.” I open the book and read: “When I was imprisoned, I thought I was the biggest scoundrel. When I got out, I realized many of the scoundrels are on the outside, and I’m human.” I read Udi’s book from beginning to end with pencil in hand, constantly making notes and drawing his image for myself.

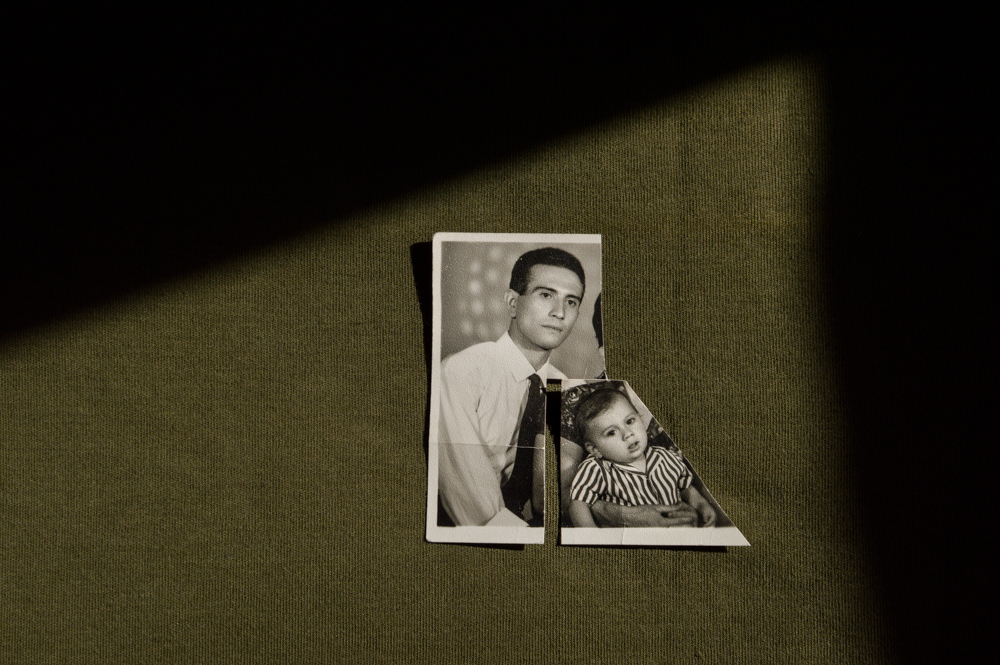

The questions increase when Udi’s daughter, Nune, doesn’t refuse and hands over to me a few of his personal belongings: manuscripts, cut-up photographs, and a pocket-size card depicting a religious icon. With these photos, I try to recover Rudolph’s childhood, and Udi’s youth and old age. Two cut-up photographs from different time periods suddenly form a complete picture in my hand; I am struck by what happened. Where is the boundary of my interfering in someone else’s life? Why did he cut a line between that child and him in the photo? Who is that woman, whom he cut out and generally left out of this story?

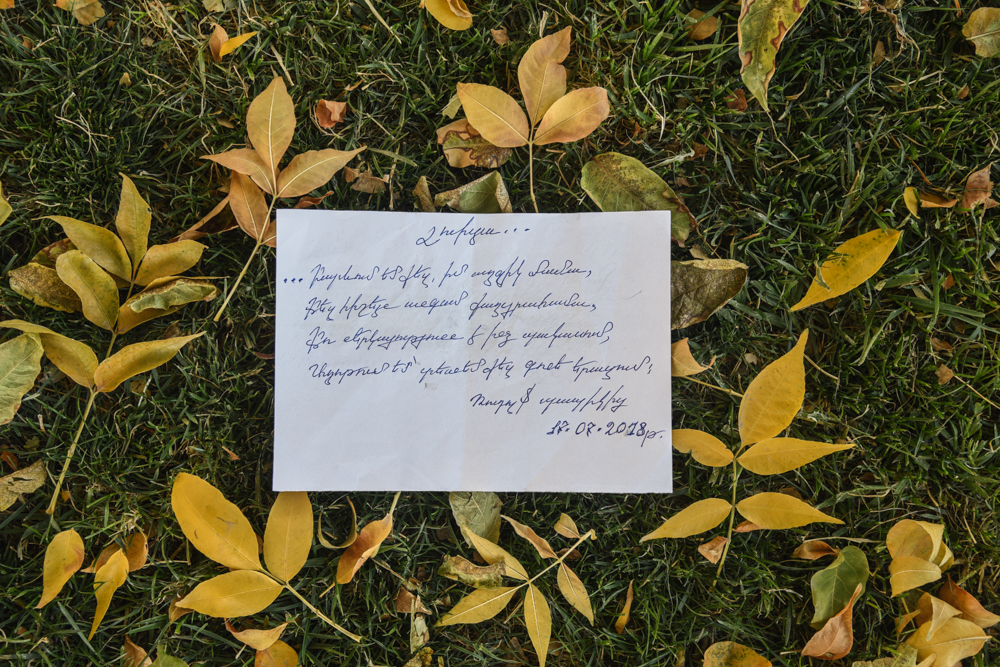

Udi didn’t like interacting with the other residents; he seldom left his room; sometimes he went down to the yard, sat in the green gazebo, and wrote down his memories. I go down that path without him, try to reestablish his presence and the absence of his presence in photographs.

This is the only photo left to Nune of her father. Rudolph was such a beautiful child that his mother often dressed him in girls’ clothes. But Udi’s story begins from the orphanage: his father was at the battlefront; his mother, in the hospital. At the orphanage, he experienced his first shock, when he saw the governess’s purse rip open and stolen bread and sugar spill out. Later, escaping from the orphanage, getting acquainted with life on the street and with criminal thugs — that’s when Rudolph becomes Udi, which wasn’t only a change in name. “He who possessed deceit and power was righteous. Wrong was he who was weak and hungry. I ran away from the orphanage…,” he writes in the book.

“In the entire institution, only I was able to grow and take care of flowers. One day, the head of the unit, deputy warden, deputy in charge of the regime, and prison officer came to me and gave me an ultimatum, demanding I destroy the flowers. The conversation turned into an argument, which became heated, turning into an uproar. They insisted that I must obey the administration’s requirements, since I’m penalized. And I was proving that, right, I’m penalized, but the flowers are not, and no one has the right to destroy the beauty of nature. The deputy warden shook his finger [at me] and issued orders to take me to solitary confinement. After sitting in solitary confinement for 15 days, I came out to the residential area and saw that not even a specimen of my flowers was left,” writes Udi. I look at the verdant tree placed in the nursing home’s corridor and mentally restored Udi’s cared-for flowers.

Luiza is one of the nursing home’s young employees with whom Udi felt a spiritual affinity, whom he sincerely admired, and to whom he dedicated several poems. I meet Luiza and I understand Udi, whose heart in the last years of his life was filled with love and warmth. “My girl mama.” This is how Udi referred to Luiza in his last quartet, in whom he saw the embodiment of his mother, his daughter, and a woman.

I finally finish his book, and cheerfully call Udi. “Allo, Mr. Rudolph, hello, how are you?” “Rudolph has passed away… who are you?” I’m shocked by this news — as shocked as I would be upon hearing of the death of a loved one. I hang up and swallow my tears. And, really, who was I to Udi? Why can’t I come to terms with his absence? After Udi’s death, for a moment it seemed pointless to continue all this, to tell a story about a person who’s a stranger to you. To posthumously gather his unfinished portrait and piece by piece bring it to life. A new experience, which forced me to knock on many doors, become acquainted with new people, because after Udi’s death, the questions multiplied.

Why did I decide to tell Udi’s story, especially after his death? Udi was the last surviving member of his family, whose soul cried out throughout his life and who chose his path in the fight against injustice, to steal from those who were stealing from the state. “Beginning from 1702, among my ancestors are Melik Safraz of Mkhitar Sparapet’s meliks** to my immediate grandfather, Zangezur’s Safraz Bey, who at the cost of their lives kept and preserved the Armenian nation’s honor and strength, culture and faith… What I’ve done is not stealing; I have taken revenge on the insult for persecuting, torturing, humiliating, taking away my health and freedom, presenting unjust and unlawful accusations and condemning me. And if anyone considers my revenge theft, then I reply that I’ve stolen from many greedy rich people, who don’t consider those who don’t have money to be people…”

I became acquainted with Udi’s daughter, Nune, on the way to the cemetery in Sovetashen. It turns out Udi had not only a daughter, but also a son — a fact neither mentioned in the book nor those who knew him knew about. Five people were present at Udi’s funeral. Nune asked to adjust Udi’s neck; she says I don’t want him to leave this world with a crooked neck.

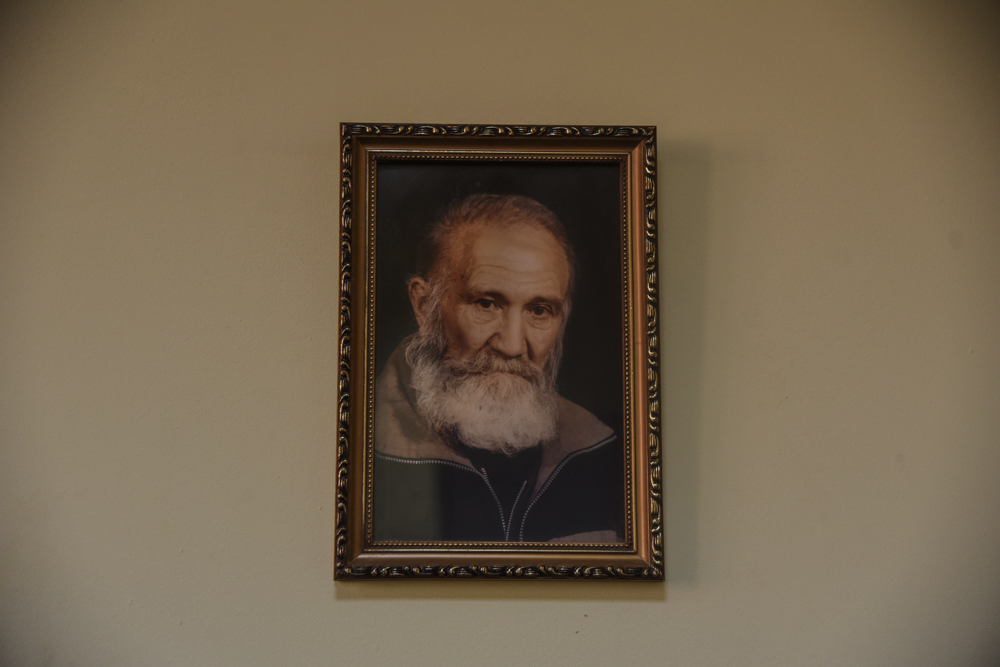

I didn’t get to know a lot about this photograph, only that Udi is 60 years old here, so he’s not yet at the nursing home, perhaps he’s just got out of prison, or a new imprisonment awaits him.

When I open Udi’s wallet, I’m surprised to see that it reminds me of a small photo album. From the start to the end of this story I’m trying to solve an equation with several unknowns: who is this woman, how can I find her? Again I call the nursing home, Nune, the employees. Eventually I find her phone number, we agree to meet, but at the last moment she declines.

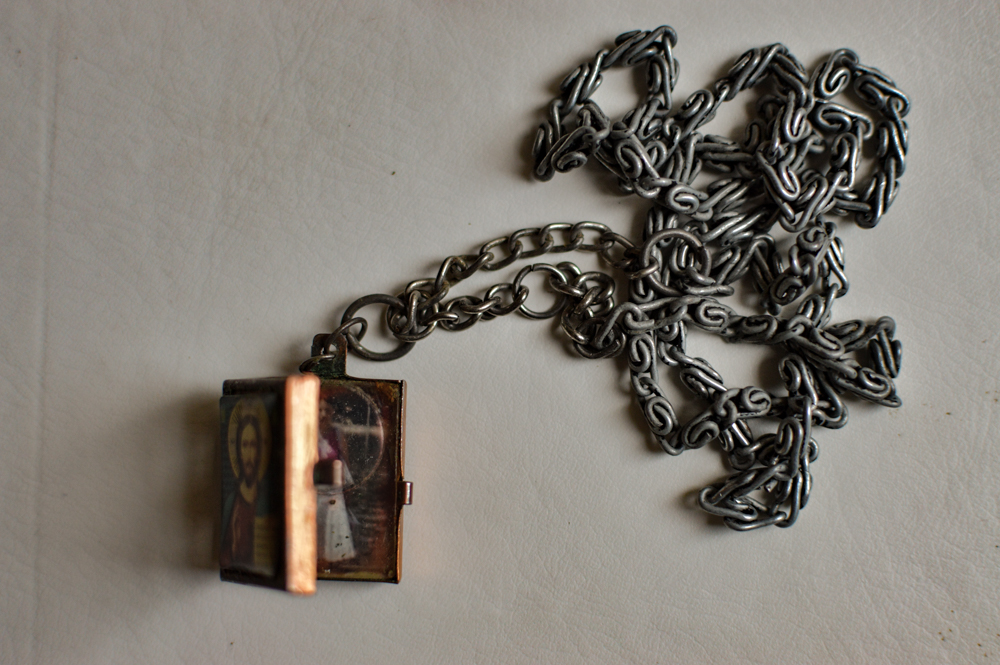

This pendant is the only object that was always with Udi, near his heart. The photos inside have faded, but their memory lives on in the distance.

Udi’s sister is searching for her brother’s plot at the Sovetashen cemetery.

The wall in Udi’s room, on which there were numerous crosses, images of religious icons, angels, and photos. During our first and last encounter, I asked him if he believes in God. He smiled and said: “God is in all of us. A person must keep his God very carefully, in his soul.”

To get to know him, I open his book again. Udi is candid in the crimes he committed; here and there he describes in detail thefts that, in his words, he committed “flawlessly” and always came out “unscathed,” but surprisingly, he was always convicted for the crimes he didn’t commit. “My first conviction was in Yerevan for [uttering] the phrase none of your business; the second, for not giving a [Russian] ruble to the guard… And so, the list of my convictions grew, from which an observer could form only one opinion of, that, ok, a man can make a mistake once, twice, but so many times?… The years passed, I was already living the fourth decade of my life. I was released on November 17, 1970, from Basargechar’s high-security prison. I came to Yerevan, I went to the house at 55 Spandaryan. My house, my possessions, everything my parents left me were gone — there was only a space equivalent to the ground. The state had sold it on account of the opening of the main avenue,” describes Udi in the book, all of whose complaints both during the Soviet Union and the days of the Republic of Armenia remain unanswered. In recent years, Udi’s complaint regarding his house was being examined at the European Court of Human Rights, whose decision he was waiting for impatiently, since he dreamt of living in his house and not at the nursing home.

The cemetery at Sovetashen became Udi’s last home. I look at the anonymous burial plots and think about Udi. What would the former prisoner who spent the majority of his life in Soviet prisons say? Did he reconcile with his restless soul, did he find his sought “Golden City”…?

*Bey is a title for chieftain, traditionally applied to leaders in the Ottoman Empire.

** meliks were hereditary Armenian noble titles.