On September 27, when I learnt what was going on, I packed my suitcase immediately and left for Stepanakert on the first day… Azatamartikneri Street. It was empty, dark, without a sound, as if I were in a ghost city and the sound of my suitcase echoed across the street. This was not the city I knew, it was another city with other people.

On that night I heard the sound of an explosion for the first time. I couldn’t believe that Stepanakert had turned into a line of contact, and we were under bombardment… “Never mind, you are sleeping, it only seems to you…” I would calm myself down like that, because I was alone on the first few days and didn’t know how to react.

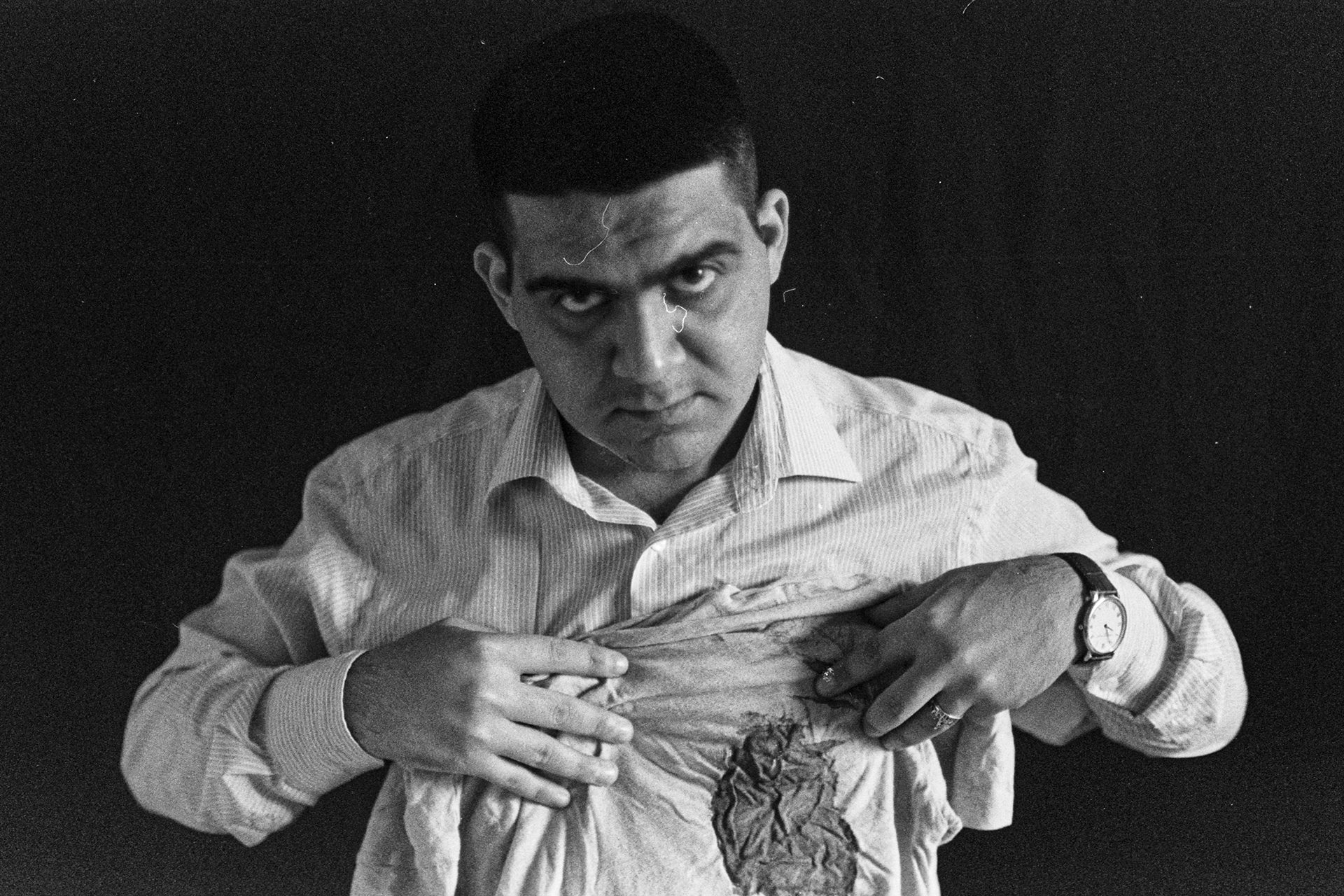

I went there unprepared. I couldn’t have imagined I would need an armour vest and a helmet, whereas there wasn’t a single place to sleep peacefully… In fact, we were sleeping right in the battle field. We would go outside at our own risk, because we didn’t understand when to go outside and when to return. We couldn’t make our way to the burnt houses and cars. We had to run back to the bomb shelters all the time. One day something happened on Azatamartikneri street (cars were burning). Just when we tried to reach the street, they launched shelling, and we had to run quickly to the shelters… Going back and forth several times, and entering different shelters, we still didn’t reach the other end of the street… The air raid siren sound was heard all the time.

I find it difficult to say what the war has taken from me, because it has given a lot… I matured greatly during that period, both as a person and a professional.

Before war, I couldn’t have imagined that, for instance, I would sleep on the floor of a school with strangers. I couldn’t have imagined I would adapt to that situation, that someday, after having left my house, I would like to stay there.

Over time you understand what is allowed and what is not. You train survival skills and learn to dodge the danger. You think you cannot overcome something, then you see you passed it like a test; you saw what happened and made a decision.

In fact, the most difficult part is treating the situation as a job, when it concerns the lives of people. You haven’t lost your house, you cannot be in the shoes of a person who has lost his house… Covering misfortune of people becomes an issue, and you face the dilemma – “Well, what am I doing here? How am I doing it? Am I doing it right?”

But… I was in a weird situation after coming back to Yerevan. I felt bad, I wanted to go back, my mind was there… My mind was in Stepanakert, Artsakh.

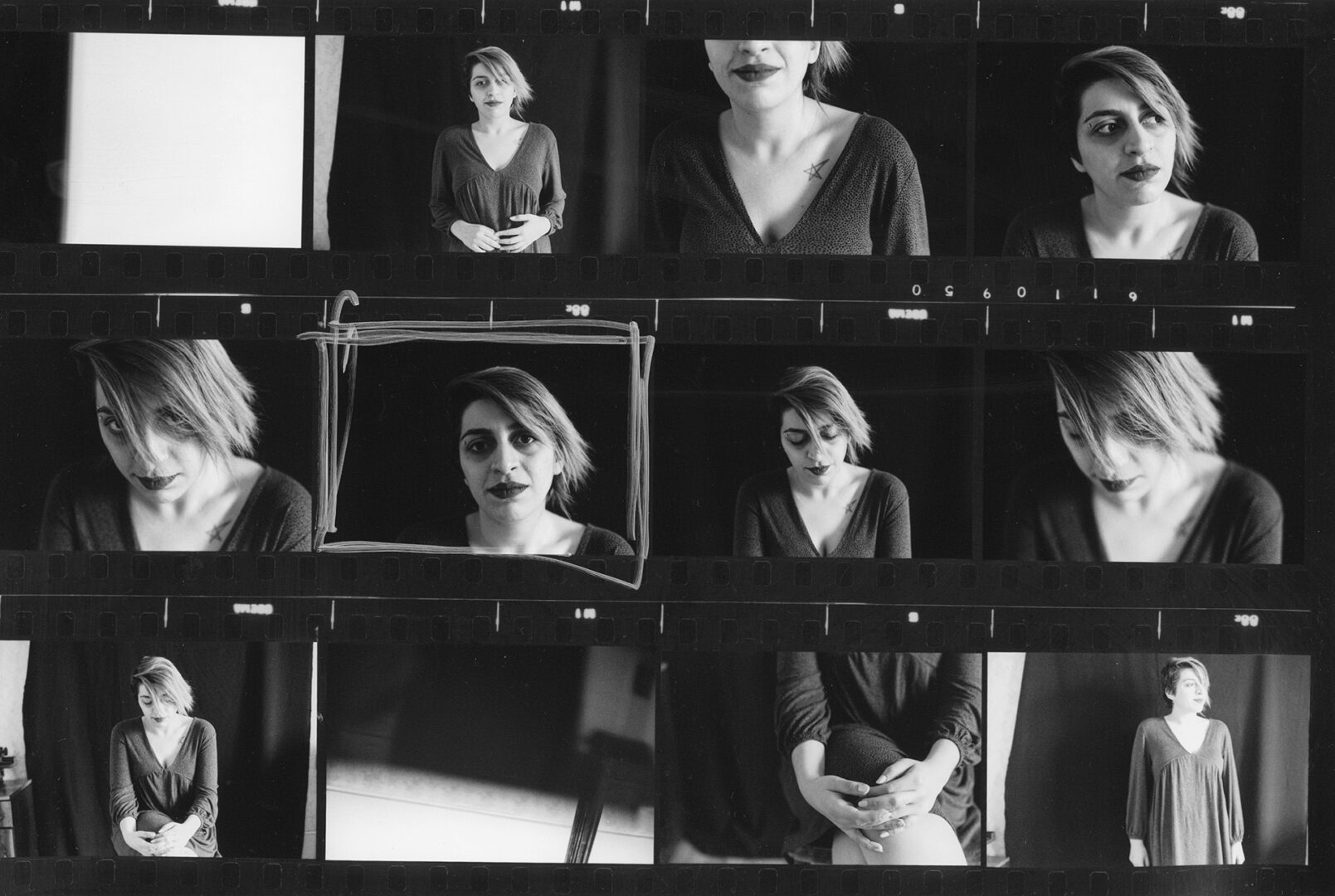

It is a totally different thing when male journalists are reporting from the frontline and when female journalists are doing it. There is a huge difference between a male war correspondent and a female war correspondent.

Once you smile at someone, they immediately say, “Will you come over to my place?” or “Shall we go somewhere…?” “Hey, I’ve come here to work.” Then again, “What are you doing here? Go, get married, have children.” Or “This is not a place for girls. Get up and go! Your job is to have children…”

“All right, you think like that, but I’ll stay, because that’s my job. I’ve come here for work and won’t go…”

My friends there would comfort me. We would talk and discuss, opening up to each other these moments. The so-called “comrade-in-arms” are those who help.

I am now trying to treat that period with humor and nostalgia, letting go of the negative feelings, no matter how negative the war is. We gather with friends, recollect, make jokes, tell about the extreme situations we went through and how we got to know each other… It’s good we didn’t have losses from our group. That empowers…