It resumed that day, in the morning… For me, the war didn’t end.

After the 2016 war… It resumed in 2020.

On our way, we saw cars driving towards the territory of Armenia. The cars were tied with stuff from all the sides. People neither spoke, nor smiled. Their faces conveyed no expression. It was sunset, and the sun was still falling in the cars driving from the opposite direction. That scene, the faces of those people, that I didn’t manage to capture, left a very strong impression on me․․․ There were so many vehicles stranded on the road and there were questions: where are they going? Why are they going? What will I do now? Shall I tell about this or not…? Shall we take photos…or not?

This is the challenge of wars. You don’t know how to tell the story. Sometimes you don’t even need to tell it immediately, as perceptions differ…

They were talking in Yerevan that people shouldn’t have left, they shouldn’t have abandoned their houses. They should have stayed (otherwise how would the soldier fight. If he didn’t know where to return or if he returned and there were no people in Artsakh and its villages, what would he do?)…

Then, little by little when you think it over, you realize that this person has witnessed the Sumgait pogrom, the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, the April war. He has either an injured person or lost one from each generation… Yes, the war was not even over… This person has lived in the war, and he certainly has the right to immediately take his family and leave… And we do not have the right to discuss his decision… The only discussion might be for understanding.

In the first days in Stepanakert, I could only see the shadows of people behind curtains and trace small distant lights… A day or two later, they were gone. The city was simply under the ground. And there was a city on the ground, but there were no people there.

There was a lot of controversy. You wake up, and there is no bread, cheese, nothing… You think it is impossible that all this may disappear and end so quickly. I would recall my experience of the Lebanese war. There, when the bombing stopped for a few hours, everybody would open their shops, do their job, then they would return to their shelters when shelling resumed.

… I know that in Lebanon there are people who go to their bomb shelters once in six months. They check canned foods, refresh water, and tidy up the space, because they know subconsciously that the bomb shelter may… After decades of war, the situation is still the same..․

… And so you go to Stepanakert and realize that… The bomb shelters are in fact basements, there are even no couches there… In case a space is in a proper condition, it isn’t furnished at all, there is even no water… So there is much to think about, because we are constantly at war. We stayed a week for the first time (we were not ready to stay so long), and it was awfully hard to come back. We felt remorse for leaving something that needed us. We stopped at the winding road of Shushi (we were three, including Mirzoyan Karen), took a picture of Stepanakert from there. It was a very painful moment; there was a feeling of desertion, but it was impossible not to come back.

Every return was so hard. After a day spent in Armenia, I had a panic attack. “What am I doing here, when I have to be there?” I felt useless, although both in Armenia and Artsakh there was not much opportunity to work, and there were so many ambiguous questions about where I should go to be of any use…

I think journalists were simply hamstrung during the war. You have a certain mission, and so you go there with an idea that you should be one of those to document the war, the one to tell about it to the world, but no one thinks so except for yourself… Neither does the army, nor the local self-government bodies of Artsakh, not even the population… You realize that this notion is only in your head, that it’s your choice, because the guys are fighting, others are doing their job, and you have to do this, that’s your duty… And no one wants or expects you to do your job, that’s not a priority. And only you and your colleagues are conscious about it, because if not you, then who would do it…?

For many senseless reasons the situation was tense for journalists, because during the live streaming Artsrun would tell us, “Don’t shoot this, don’t do that, if you shoot, they will hit the area a minute later…”

They made enemies of journalists… Once you approached a building, they immediately told us if we shot, Azerbaijani forces would hit us the next day… There was another clash as well: at the same time, priority was given to a foreign journalist. They probably thought the locals were not professional, accountable, nor were we creditable… It’s embarrassing… Foreign journalists will leave after all in a few days and take some fragments with them, and it will end there… While we document everything from A to Z…

When the people were being evacuated from the Europe Hotel, I was told my camera would be smashed if I showed up there again. But the next day I saw BBC’s full coverage going viral, where both the building and its name were visible… Perhaps, we lacked experience, perhaps we should take it easier, and needed not to rush in…

We missed so many things for so many senseless reasons…

The war didn’t take anything from me… It gave me… It gave me the truth about living in a potentially tragic situation, about how foolish, disorganized, irresponsible, improvident, and impractical we are… And unfortunately, we keep being the way we are.

It certainly gave me the feeling of helplessness. When they say we didn’t consolidate efforts after the 2016 war, hence we had the 2020 (at least in the media), you want to say if the war resumes in 2025, we will still be the same…

We do not have a priority.

We have an issue to be earnest. We are neither honest with ourselves, nor towards each other. For years, we have been living in a country unaware of its borders.

The war has an interesting course․․․

The emptiness and darkness of Stepanakert in the first week was then enlivened with characters that appeared during the second and third weeks… Heroes appeared, so did the brave, some moderate people, as well as radicals… That’s when you realize that war becomes a system… You change, your attitudes change.

In the third and fourth weeks you see people’s anger, aggression. You feel they have crossed the line, they have already buried many people, lost many, they are helpless… Here you appear in a totally different situation… You become a witness, but you don’t tell… And you meet a soldier who gives you soap…

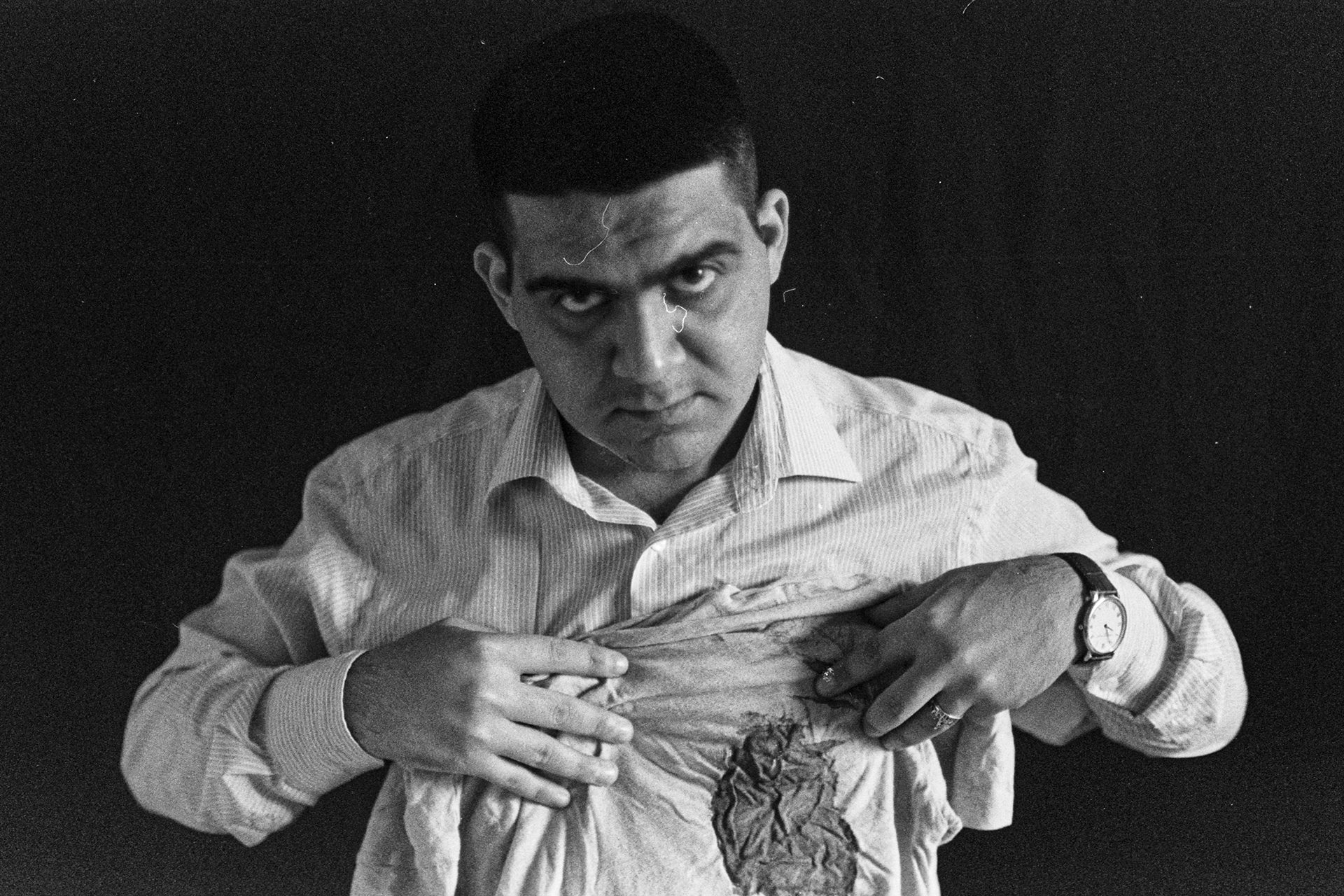

It was the first week; we happened to be in the second line where there were volunteers who had come to get military outfits to leave for the front line right away. I didn’t take a single shot the whole time. I mean, I took some pictures, but those were images they wanted me to capture. I shot for them, because those guys were getting their uniforms at that moment. They had to leave, get into the truck and drive to the front line. It was probably the hardest moment for all. And if before they told me not to shoot them, everyone there asked me to take his picture. “Please one more, like this, and one more with my friend…”. And you are not a journalist any more; you are first of all a chance for them to draw away their difficult emotional state. Secondly, you also become a tool… Perhaps it is their last photo…

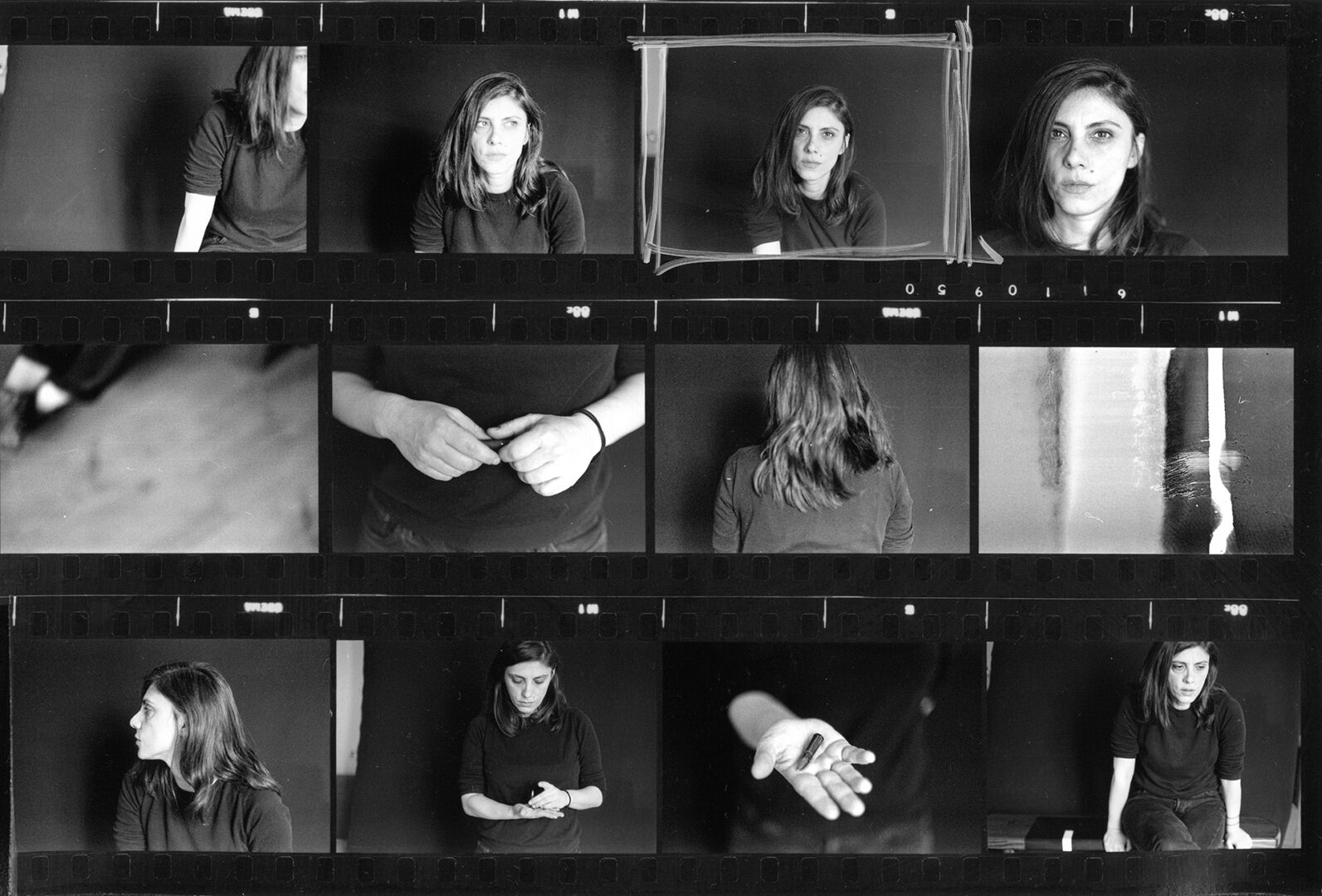

I think the presence of female journalists in the course of war is very important. They talk to you differently; they are more frank, more melancholic, at times they are tender, at times cruel… (…one could grab a whiskey and call on you, come to your hotel…)

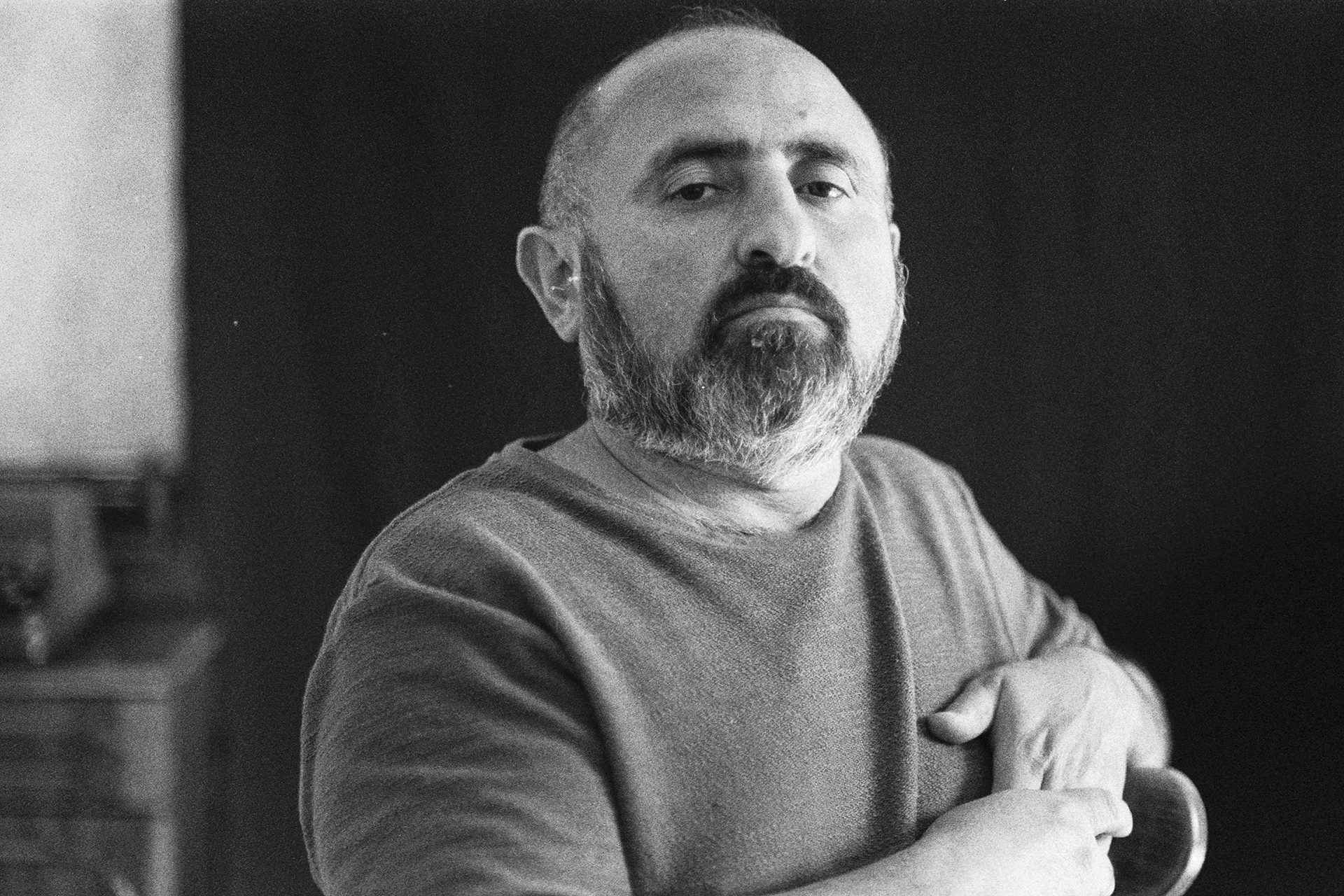

We always see the soldier standing strong, ready and steady, and only then do we see him wounded, limping or in a wheelchair… Or dead. While the soldiers who were injured and badly wounded, will return to society tomorrow or the day after… We do not see this period. It is a whole life, and I don’t know how to tell about it… He fights his other war, that is invisible to us, and we don’t see that. Yes, we utter the word “disability” superficially… But these guys who have already lost a hand, a foot, their human shape, they should return to society… This is the most truthful image of the war, which we barely see… We don’t see it firstly because we don’t want to… If we saw, we would, perhaps, think differently; we wouldn’t think that going to war was a heroism.

…After all, we have to understand what will be the price of peace… Will it be for the cost of others’ lives, new lives, Artsakh…? We have to give something for or in return for it, don’t we…?

… Perhaps we should now start the conversation that we haven’t had for 30 years? We should ask ourselves, “What do we give for peace…?” I assume you cannot earn or be gifted peace believing in Nazar the Brave’s luck…